Aberfan: When the Mountain Moved and Nobody Paid

21 October 1966

At 9:15 on a Friday morning, a mountain of coal waste buried a primary school in Aberfan.

One hundred and sixteen children went to school and never came home. They weren’t killed by a storm or an earthquake. They were murdered by the National Coal Board.

The Mountain of Shit That Shouldn’t Have Been There

For years, the Merthyr Vale Colliery had been dumping its waste on the hillside above the village, millions of tons of coal slurry and rock.

By 1966, seven massive spoil tips loomed over Aberfan.

Tip Number 7 was the monster: 111 feet high, built on top of natural springs.

They knew. Their own safety rules said not to do it.

The ground was soft, soaked through by constant rain. The valley flooded all the time, the water running black and greasy.

The villagers knew. Christ, they knew. They warned the Coal Board again and again but were told to shut up or the mine would close, and in a pit village, that was a threat to starve. So people bit their tongues. And the tips kept growing.

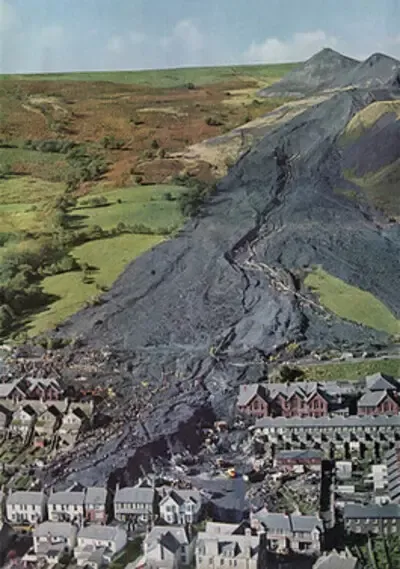

Aberfan in the days immediately after the disaster, showing the extent of the spoil slip

The Day the Mountain Fell

It had rained for weeks. On the morning of the 21st, men at the tip saw it starting to move. They cancelled the day’s work, but it was already too late.

At 9:13 a.m., it went.

A wave of black slurry, thirty feet high and moving faster than a car, tore down the hillside.

It hit the Pantglas Junior School and filled the classrooms with liquid coal.

It was the last day before half term. The children were just settling into lessons.

One hundred and sixteen children. Five teachers. Twenty-eight other adults.

Most suffocated.

Parents clawed through the muck with their bare hands.

The last live child was pulled out at eleven o’clock.

It took a week to find all the bodies.

They buried eighty-one of the children in two long trenches.

Ten thousand people came to say goodbye.

The Three Indignities

The official inquiry, the longest in British history, heard 136 witnesses.

Its conclusion: the disaster “could and should have been prevented.”

They called it “ignorance, ineptitude, and a failure in communications.”

Posh talk for criminal negligence.

The National Coal Board fought them every step of the way.

Lord Robens, the chairman, lied under oath.

The tribunal was told to ignore his evidence.

No accountability. Nine NCB men were named as responsible.

Not one was sacked. Not one was prosecuted. Not one spent a day in jail.

They killed 116 children, and nobody paid. \The cash insult. They offered the parents money. Fifty pounds for a dead child.

Later raised to five hundred and called “a generous donation.”

The public donated £1.75 million to a disaster fund for the families. \The theft. The government then stole from that fund.

They forced the victims to pay £150,000 to clear the other tips, making the grieving clean up the murderer’s mess.

That money wasn’t repaid until 1997. \

Why This Still Burns in My Mind

I was almost twelve.

I remember my Nan crying watching the disaster unfold on the TV.

I remember the little coffins.

Four years later, on my second day in the Army at Harrogate, some English kid made a joke:

“What’s black and eats children? Welsh coal tips.”

I went for him. Tried to headbutt the little bastard. They had to drag me off.

That wasn’t just a bad joke, it was what they thought of us.

Our dead children were a punchline.

Aberfan wasn’t an accident.

It was a choice, a choice to put profit before people, to ignore the poor, to protect the powerful.

It happened because, to the men in charge, we simply did not matter.

And that’s why, nearly sixty years on, we must still say their names.

Originally published on Catsandbirdsandstuff.com on 21 October 2025